St Werburgh is a female saint of the 7th century associated with many places in the Midlands of England which are close to a variety of Coptic Orthodox communities. These include Stone, Trentham, Hanbury, Weedon and Chester.

Her mother was Ermenilda, a Christian princess and daughter of Erconbert, the King of Kent, and of St Sexburga, his Queen. She had married Wulfhere, the pagan prince of the Kingdom of Mercia, and son of King Penda, whose violence and warfare had been the cause of the death of five Christian kings.

St Werburgh was born in a wooden palace at a place called Wulfherecester, or Wulfhere’s castle. It can still be found outside Stone in Staffordshire, and is known as Bury Bank. It is an Iron Age fort, much older than the time of St Werburgh, but as an ancient fortified and political centre it was reused by the invading Anglo-Saxons in the 6th century. Wooden buildings would have been constructed inside the fort, surrounded by banks and ditches, but nothing remains of this period, and the fort would not have been occupied at the time Werburgh for very long. But she lived here as a child, and grew up here as a young woman, much influenced by her mother, and becoming a Christian like her.

St Werburgh had three brothers, Ulfald, Ruffin and Kenred. Wulfhere objected to his sons becoming Christians and wished rather that they should grow up to be warriors like himself, and serve the old Anglo-Saxon gods. But Ermenilda did what she could, with discretion and carefulness, to develop in them Christian principles and virtues. As a child and a young woman, St Werburgh showed no interest in the wealth and importance of her royal status. She preferred to learn and practice the Christian faith at her mother’s side, and attend the services of the Church with her, and take part in acts of kindness and charity as her mother’s faithful partner and companion.

The great St Chad was a hermit in the forest near the royal residence of Wulfherecester, at Bury Bank. The two older boys, now young men themselves, would ride into the forest and sit with St Chad who prepared them for baptism at his little chapel and cell among the trees, and eventually performed the sacrament there and made them Christians. At the same time, St Werburgh was of an age to be considered for marriage, and her beauty and character led to many putting themselves forward. But St Werburgh had already determined in her heart that she would commit her whole life to God and rejected them all.

One of those who sought to marry her was a powerful noble called Werebode, and he was neither used to being resisted, nor willing to accept it. He was sure that it was her Christian faith which had led her to reject him, and he decided that he would watch for an occasion to accuse her to her father. He noticed that the two princes were riding out into the forest, and meeting with St Chad, and he reported this to Wulfhere, suggesting that they were intriguing with him to overthrow their father, and claim the throne for themselves, and make the Kingdom Christian.

Wulfhere was easily roused to uncontrollable anger, and he rode out with Werebode to find his sons. He found them kneeling in prayer at the chapel of St Chad, and demanded that they abandon their faith and return to the pagan religion. Nothing could move them, and in his fury Wulfhere called on Werebode to kill them there, and so they received the heavenly crown of martyrdom, while Wulfhere rode back in anger to his palace. Ermenilda and St Werburgh were overcome with sorrow at their sudden loss, even while they were filled with joy at the faithfulness of the two brothers to the end. They set off into the woods and found St Chad praying at the side of the bodies of Ulfald and Ruffin. Together they buried the bodies and raised a mound of stones over them.

This chapel and the hermitage of St Chad were at the place where St Michael’s Church, built in 1738, now stands. The stone cairn which marked the grave of St Werburgh’s two martyred brothers, might have been the reason for the name of the town which grew up here being called Stone. A church was soon built over the grave in 670 A.D., and this was replaced in 1135 A.D. by a Priory, or small monastery. The only visible remains of this priory are found in the cellar of Priory House. This is another location associated with St Werburgh, and the place where she buried her brothers, and sought the wise counsel of St Chad.

Wulfhere realised the enormity of what he had done and was filled with remorse. The witness of his sons, no less than his wife and daughter, led him to be instructed by St Chad, and he too was baptised, and became a changed man. When he became King of Mercia himself he rooted out the traces of pagan worship, and established churches throughout his kingdom, and in Stone, where his sons were buried.

St Werburgh determined to follow her own desire for the monastic life and was given the permission of her father to join the famous convent at Ely in East Anglia. Her aunt and her grandmother were monastics there, and it had been founded by her great-aunt. It was because of these family connections that Wulfhere and Ermenilda were pleased to entrust their daughter to the convent there. Wulfhere, with many of his nobles, escorted her to Ely, and at the door of the Abbey she was greeted by the Abbess, and by St Chad, who was now Bishop of Lichfield. She removed her royal robes and put on the clothing of a novice. The next year the royal family returned to witness her consecration as a nun.

In 675 A.D., King Wulfhere died, having committed the last years of his life to the Christian faith, and Queen Ermenilda took the opportunity of her widowed status to follow her daughter into the Abbey at Ely. The Life of St Werburgh records that…

Her only diligence and solicitude was employed in avoiding all things which might displease the eyes of her heavenly Bridegroom, for whose love she despised gold, jewels, rich attire, and all other vanities admired by the world. All her thoughts were busied in this one thing, how she might excel her religious sisters in observing silence, abstinence, watchings, devout reading, and prayers. Which holy design having compassed, insomuch as she was as far exalted above them in these and all other virtues as in the nobleness of her descent, yet she thought so meanly of herself, and was so free from any arrogance or pride, that she showed herself always ready and willing to obey all, and cheerfully undertook the vilest offices, among which a charitable care of the poor and needy, to whom she was a pious and tender mother, took the principal place. In a word, through the whole course of her life her conversation was such as showed that though her body moved on earth yet her mind was always fixed in heaven.

In 679 A.D. the Abbess Etheldreda passed away, and St Werburgh’s grandmother, St Sexburga, was unanimously elected to succeed her. And then, after some time, when St Sexburga had passed away, her own daugher, Ermenilda, the mother of St Werburgh, took over the ministry of Abbess. Through this time St Werburgh continued in humility and devotion to perform all the service to God and others of the monastic life.

When King Wulfhere had passed away, his youngest son, Kenred, was not of an age to become king, and so his uncle, Ethelred became king. He was committed to the Christian faith, and having a very high opinion of St Werburgh, he wanted her to organise and direct all of the convents in Mercia in the same way he had seen at Ely. It took a little while to persuade her, but she gave herself to the task with all of her energy. The King enabled her to establish three new monasteries at Trentham, at Hanbury in Staffordshire, and one at Weedon in Northamptonshire. Weedon was a royal palace which King Ethelred placed at her disposal.

It was said of her…

She carried all her daughters in her heart, loving them as though they were indeed her own children, and teaching them virtue by her own example. She possessed in their fulness the spirit of peace, kindness, joy, and love. She was cheerful in tribulation, overcoming all difficulties by faith, and rising above earthly trials by fixing her heart on heaven. She preferred fasting to feasting, watching to resting, holy reading and prayer to recreation and dissipation. In God she possessed all things : He was her consolation in sorrow, her counsel in doubt, her patience in trial, her abundance in poverty, her food in fasting, her medicine in sickness.

The monastery at Trentham was on the site of the present parish church, and in the churchyard is the base of an Anglo-Saxon cross which dates from this time. The modern park at Trentham is on the site of St Werburgh’s monastery and she would have known some of this landscape, though the lake is a much later development.

The monastery at Hanbury was on the site of the present parish church, but although St Werburgh was buried here with great honour, the invasions of the Danes in the 10th century led the nuns to take her holy body to safety when the monastery was destroyed.

There is no trace of the monastery at Weedon in Northamptonshire. But the same monks who later established a small monastery after the Norman conquest, which has disappeared as well, were the same monks who established a monastery in Chester around the church in which St Werburgh’s relics had been transferred. The monastery of St Werburgh would have been on the site of the present parish church.

When St Werburgh started to feel that the end of her life had come she insisted that she should be buried at the monastery in Hanbury, wherever she died. In fact she was at the monastery of Trentham when she passed away on February 3rd, 699 A.D. The nuns of Trentham were unwilling to give up the body of their beloved mother, and locked the gates of the monastery and the door of the Church. But when the sisters from Hanbury arrived to collect the precious body they found that the gates and doors opened to them, and those who were supposed to be on guard had fallen into a deep sleep.

So she was buried at Hanbury and many miracles were performed at her tomb. It was said, “In this place sick persons recover health, sight is

restored to the blind, hearing to the dumb, the lepers are cleansed, and persons oppressed with several other diseases do there praise God for their recovery.“

Devotion to St Werburgh increased, and it was the common wish that her body be translated to a more fitting place of burial, and so her youngest brother, Kenred, who had now become King of Mercia, came with a great crowd of nobles and clergy to witness the reburial of his sister. She had lain in the ground for 9 years, but when they uncovered her remains they were found uncorrupted, as if she had just fallen asleep, and her clothing was as fresh as when she had been buried. The priests who had accompanied Kenred carried her remains in procession and she was placed in a new shrine which had been constructed.

King Ethelred had abdicated in favour of Kenred in 704 A.D. and had become a monk in the monastery of Bardeney in Lincolnshire. King Kenred himself, in 709 A.D. after the translation of his sister’s remains and the discovery of their incorrupt state, gave up his kingdom, and with King Ina of the East Saxons, set off on foot as pilgrims to Rome. It took them a year to arrive, and in Rome they became monks themselves and spent the rest of their lives in spiritual and ascetic endeavours.

St Werburgh remained undisturbed at Hanbury until 875 A.D., and her shrine was a place of pilgrimage and prayer. But when the fierce and pagan Danes invaded the East of England, many monasteries, including that at Hanbury, were under threat of destruction. Alfred the Great was King of much of England, and the Kingdom of Mercia no longer existed. But Ethelred was the Earl of Mercia, and he had the shrine of St Werburgh carefully carried to the old Roman city of Chester where he built a church to house it. The shrine continued to be a place of even increasing pilgrimage, from kings and common people alike.

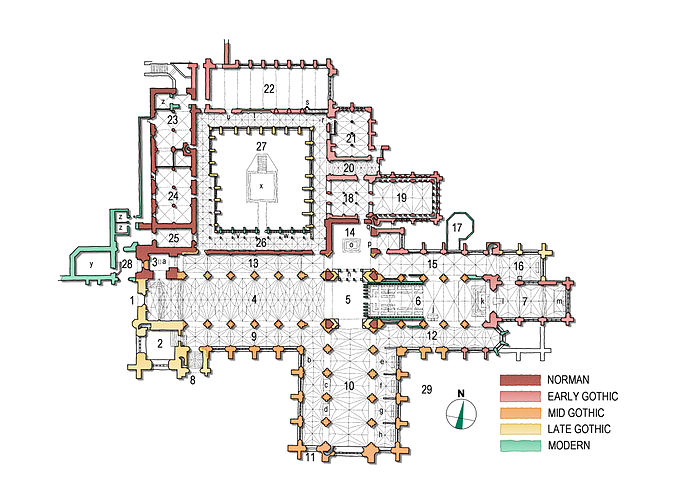

In the time of King Edward the Confessor a new monastery and church were constructed in her honour by Leofric, the Earl of Mercia. While in 1093 A.D. an even grander church was built. It is said that “in 1180, a terrible fire having broken out in Chester which threatened to destroy the city, the inhabitants fled to her for protection ; upon which the monks, taking up her body, carried it in procession to meet the raging flames, which immediately subsided, and the town was saved.”

In the 16th century, when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries and introduced Protestantism the shrine of St Werburgh was destroyed and her holy relics thrown out like rubbish. Today some fragments of her shrine have been reconstructed, and the Abbey Church is now an Anglican Cathedral.

One miracle associated with St Werburgh has to do with a flock of geese that were troubling the steward of the monastery at Weedon. They were settling on the fields and easting all the corn. The steward had tried to chase them off but with no success. St Werburgh instructed him to command them in her name, and so he went and shouted, “In the name of Lady Werburgh!” and they immediately left the fields, and walked in procession into one of the barns where they settled down. The next day St Werburgh came to the monastic farm, opened the door of the barn, and blessed the geese and they all took flight and settled noisily on the roof. St Werburgh understood that one of them was missing, and she questioned the steward, who admitted he had killed one that night and intended to eat it. The lifeless goose was brought to St Werburgh, and touching it she restored it to life and it flew up and the whole flock departed together.

May the prayers of St Werburgh be with us all.

One Response to "100 British Saints – #5 – Werburgh"