The problems faced by young people within the Orthodox Church are not unique to them. They are experienced by those with an Orthodox faith, those who belong to other Christian communities, those adhering to other religions, and by those with no faith at all except in a materialistic explanation of the universe. They are, to a great extent, a consequence of living within Western societies that have lost connection with the Christian philosophical, spiritual and theological basis on which they were formed. This certainly does not mean that if only every person became a member of a Christian community all of our social and personal problems would be solved. On the contrary, many of the problems we face as individuals and communities are due to the corruption and subversion of the Christian message over many centuries by those who consider themselves Christian There is a real sense in which both the modern atomisation of society and the loss of authority is actually a development of Protestant Christianity in the West. It is not enough simply to attend a church or congregation. Nor is it enough to call ourselves Christian without a personal commitment to the authentic Christian Gospel, or Good News. That which was first proclaimed in the Apostolic age on the basis of the experience of life in the presence of Jesus Christ, the teacher, miracle worker, and incarnate Word of God.

Nevertheless, even if many Christians have failed to teach and live the true Christian message and life, this does not mean that there is no such transforming spiritual path at all. It only means that many Christians and churches have obscured it. It remains what it always was, a narrow way, not always easy to find. But when we discover it we understand that it leads to the true experience of authentic humanity in union with God. When I reflect on the significant issues and questions of our time, those which cause confusion and distress to many within our own Orthodox community, and in the society around us, I cannot respond other than as a priest and pastor, a shepherd of souls. I do so because I am convinced by my own experience and that of others, that the authentic and Apostolic Orthodox Christian philosophy, spirituality and theology has the means of bringing clarity to these issues, and healing and transformation to every soul. This is because above all, it is not a collection of prescriptions and commandments, but the means of entering into a transfiguring relationship, leading to union with the divine life and the unceasing communion with God.

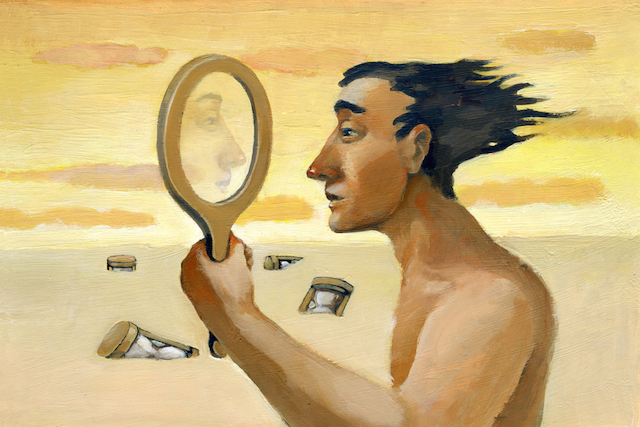

Many of the problems which we face in our post-modern society, one in which there are supposed to be no certainties, are to do with identity. These can be related to larger societal movements and the tensions that exist between migrants and citizens, between men and women, between young and old, between nations and classes. But more painfully, these also develop as personal and psychological conflicts and confusions. At the heart of many of these interior struggles is the seeking after an identity. We need to know who we are. This is surely why so many of the issues in our society have attracted a label to themselves, so that people can say – I am a….! These go beyond simply describing a personal attribute or interest but take on the nature of an identity.

We can usefully consider the devastating neurological condition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Someone who suffers from this illness begins to lose connection with their memories, among other symptoms. In not being able to recognise other people, even close friends and family, because of the loss of memories of them, the sufferer also loses their own identity. Their identity, who they are, is not independent of other people. Rather it is an expression of their relationships with others, and the experience and memory of those relationships. When a person cannot remember these relationships then everyone becomes a stranger to them, and every moment has the anxiety of a new encounter. Undoubtedly the true person remains within the soul, but is unable to express him or herself through the failing structures of the brain, and so loses the identity which is expressed in relationships with others and with the world.

Something like this, it seems to me, is happening in the hearts and minds of countless people, though not as a result of Alzheimer’s Disease. In a society in which it is insisted that nothing has ultimate meaning, and where every choice seems possible, so that it becomes impossible to make a choice. When I was young nobody had a mobile phone. Even the military application of mobile communication required a device the size of a suitcase. When I first obtained a mobile phone, it was through my work as an IT specialist, and the choice was very limited, and the phones were very simple. The choices were easy. Shall I have a mobile phone or not. And then after a few years the choices remained very straightforward. Shall I have this one or that one. But now there are so many phones and the choices are so wide and varied that it becomes harder not easier to choose a phone. It seems to me that whatever choice is made will necessarily bring about a level of disappointment and anxiety because even in making the choice of this phone, I have not chosen others that I also like and desire.

It is not so much that we are losing our memories and so our identity. Rather we are presented with such an unlimited offering of what we might be that we find ourselves unable to make a choice, and even in the act of choosing we find ourselves filled with anxiety and a sense of the loss of other opportunities. Rather than being left with fragments of memory, we are offered fragments of identity, and so we never become the person we are, just as a sufferer of Alzheimer’s slowly loses the identity which she or he had once possessed.

The Western world presents an unlimited choice and demands that we choose even when we have no basis for a choice. But much more than this. The Western world now confuses who we are with what we do or think or believe. The unlimited choices we are presented with are not enough to sustain our true identity, and so even in choosing we find ourselves isolated, confused and fragmented. Who we are, who I am, is not the same as what I do, or think, or believe. But post-modern materialistic society does not believe that we are anything more than what we do, or think, or believe. It cannot, because it is committed to a worldview in which only the material exists. Therefore, who I am must be the same as what I do, or think, or believe.

One of the main reasons for the conflict in identity in these times is this reduction of human identity to a utilitarian basis. When we think that the person I am is only based on what I am for, then I am reduced to a thing, and if I feel that I have no use then I have no purpose for being, and my identity is lost. I am no longer a person at all. If identity is based on utility, then those who are not useful are not persons. This was how the evil ideology of Nazism was able to classify entire populations as being not-persons and treat them only as disposable and consumable things. First of all, the mentally and physically disabled, then those with opposing social and political views, then homosexuals, and finally Gypsies and Jews. This was only possible because the modern materialistic perspective has to conflate identity and utility. A person can have no ultimate and absolute worth because he or she is only a collection of atoms and energy, and therefore can only be of utilitarian worth, in so far as he or she is useful to the ends and ambition of a society.

But the Orthodox Christian understanding of anthropology, which I consider to be true and life-affirming, is that we are not simply what we do or what we are for. Our worth is not found in our usefulness, or our belonging to various categories or groups. We have a worth even if we can do nothing, and do not belong to any group, or have no idea what we are for. When we think in terms of utility, and these ideas and attitudes can be found even in Christian communities, then we say of ourselves…I am a Doctor. Or I am a Deacon. Or I am as Student. Or I am a Socialist. Or I am a Libertarian. Or I am a Feminist. Or even I am a Heterosexual. Or I am a Homosexual. Or I am Transgendered. In a materialistic world this makes sense. If I am nothing other than what I think or do, then this is what I am. But none of these terms adequately describe even my thoughts and acts. They fail to give me an identity even while I use the term to identify myself. If I am only a Doctor, and place my identity in this function and activity, then what happens to me, to my identity, if I cease to be a Doctor through some circumstance? What happens to my identity if I move to another country and cannot gain permission to practice as a Doctor? Who am I, in such a circumstance? And what happens to my relationships as parent, child, husband or wife, when my identity is found in my being and doing the activity of a Doctor?

Even within the Church community, if I identify myself, and root my personhood in some aspect of service, what happens when I cannot serve in that way, or if my service is challenged or rejected? What do I have left, to sustain my identity, or even my Christian faith, if it is based on what I do and not on who I am? In a practical sense, this is why there are arguments about who has the microphone in the choir, or stands beside the priest at the altar, or takes charge of the censer. If I am only what I do, then I am nothing and no-one if I am not able to do something!

Of course, it is necessary to describe what we do, but there is a difference between saying – I am studying at this university and I am on this course, and saying – I am a student, as if it defines and describes who I am in myself. If I say I am a student what am I trying to say about myself? That I am intelligent? That I am part of an educated elite? That I expect to get a good job? That I have an excuse for not working? Perhaps all of these are true, but if I am defined by my student-hood, if I really am a Student, then who am I if I fail a course? Who am I when I do badly at an examination? Am I worth less than others, and do I become worthless?

The other words we can and do use to describe ourselves also fail to express who I am in any meaningful and transcendent sense. Must I be a socialist, or a capitalist? Must I be a feminist or a misogynist? Can I not be myself, with a wide variety of changing and maturing views that do not define me, and cannot describe me as I am? When we adopt a utilitarian perspective on personhood then we cannot help but be formed into the narrow mould of whatever description we apply to ourselves. If I am a socialist then I must hold these views, and I must reject these views. But must I be a socialist? And if I am not a socialist must I be a capitalist, and must I hold these views, and must I reject these other views?

I can certainly become a socialist, and read all the necessary books and texts, and have all the obligatory opinions and attitudes, but this will not make me the person who I am. Instead, it will make me the person who does these things and has these views. It will make me less the person I truly am, and only into a copy of some model of a person that does not exist. The more I become some “thing”, the less I become who I am. Because Orthodox Christianity, authentic Christianity, teaches us that we can never be reduced to a thing.

And this applies also to categories such as obese, autistic, heterosexual, homosexual and transgender. None of these are suitable to describe a person according to Orthodox Christianity, because they reduce our personhood merely to what we do, or think, or feel, or some condition which is accidental to our personhood, and not intrinsic to it. I believe that it is clear that in the life to come with God there will not be sexual experience, even though the personal intimacy will be closer, and not clouded by our physical weakness. We will know each other more than has ever been possible in this life, and that will not require sexual relations. The Lord Jesus himself says…

In the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are like God’s angels in heaven.

This shows us that our personhood is not dependent upon sexual experience, even though we live as sexual persons in this life. In a life to come the words heterosexual, homosexual and transgendered will have no meaning and can have no meaning because sexuality will not have a place in the eternal world, even though we will certainly have bodies. But we will also certainly be the same person that we are in this sexually embodied state. All of these terms harm us when we use them in a utilitarian manner. Many of those who are physically disabled in some way express this very urgently. To be unable to see clearly, for instance, is not to have become a different category of person. It is something accidental and on the exterior of our true personhood.

One person with some physical disability says…

It’s frustrating when people see physical disability as anything other than a few logistical difficulties that I have to be creative with and find ways around. It doesn’t define my motivations, ambition and identity, so why should anyone have this preconception?

Such a person does not want to define themselves by one or two physical limitations and does not say of herself – I am disabled. There is so much more to her than this one thing, as she describes. There is also a difference between saying, I have been diagnosed with limited vision, and sometimes this makes it a bit hard to get about and saying – I am a blind person as if it described in one word all that we a person is. Once again, the Orthodox Christian view of the life to come gives us an understanding of what our true personhood is like, since we do not believe that those limitations of body and mind which can afflict us in this life, will be experienced by us in the truly human life to come. They may certainly limit and affect our experience of life now, but they do not define us, because they are provisional and temporary.

From the perspective of Orthodox Christianity this same perspective applies to the categories or labels of heterosexual, homosexual and transgender. Even if it was allowed that these categories reflect a physiological reality, and this will be considered in due course, these physiological realities cannot describe our interior and authentic personhood because they will not be present in the life to come. Even if I consider myself a heterosexual now and in this experience of life, and even if others consider themselves to be homosexuals or transgendered, this will not be a reality in the future, and so cannot define my person, or that of others. If I consider myself a heterosexual, then it does not say who I am, it only says something about how I think and act and feel, and even if it were an important aspect of what I thought and how I acted and felt, it could still never describe who I am. When I am reading a book, am I reading as a heterosexual, or as the person I am? When I am cooking the dinner for my family, am I preparing the food as a heterosexual, or as the person I am? There are, in fact, only a limited set of contexts where it is important to consider that I am or am not a heterosexual. Likewise, the person who has limited mobility does not read a book as a person who needs a wheelchair, but as the person they are. Nor does the person with limited mobility enjoy the countryside or the seaside, other than as the person they are. Their limited mobility may affect what they can do, but it does not describe who they are in themselves.

All of these terms, including heterosexual, homosexual and transgendered, are words of utility and not of identity. Even without beginning to consider what they mean, and what it means to describe ourselves in this way, we can say that they cannot and do not describe the person I am, and can only describe things I do, things I think, and things I feel. We cannot experience or discover our identity when we define it only by accidental and provisional aspects of our life and humanity. We harm ourselves, and are harmed, because these utilitarian terms prevent us gaining an identity, even though it seems they give us one. What they provide is a false identity, because we cannot be defined in our personhood and identity by our utility. I am not just what I do. I am this person that I am, even if I do nothing.

What do we believe, as Orthodox Christians, and with the experience of the transforming power of God? It is that utility, what we do and what we are used for, cannot form our identity. But that our identity, who I am, is formed according to God’s purpose and intention through union with God and an eternal relationship with him. If it is God who has made us, and I believe that this is so, then even before we can do or say or feel anything, we have a value and meaning and purpose in our identity, because we are created for a relationship with God, and in a relationship with God.

God is unknowable in his essence. We are created by God. He is beyond our understanding and comprehension. How can we even imagine the existence of God as he experiences his own existence as the Holy Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. How can we have any understanding of what it means for God to exist beyond all existence, beyond space and time. We cannot know any of these things. In his essence God is hidden from us. But God makes himself known to us. He enters into a relationship with the creation he has brought into existence, and he creates each one of us in a relationship with him. God makes himself known to us, even though his inner essence remains hidden, and we say that it is by his divine energy that he reveals himself as a Trinity of divine persons, one God, who made us in love to love in a union of love with him.

But man is also unknown to himself in his essence. We do not know truly and deeply all of the secrets of our existence. Of course, we can study the body, and make some investigation of the mind and brain. But we do not know who we really are, because we can only discover who we truly are by the experience of union with the one who created us and called us into existence in his purpose. It is only by experiencing the divine energies that our authentic human person and identity comes into being and focus. If we have been created by God, and I believe that we have, then we can only find our identity in a relationship with this God.

Even more than this. We can only come to know others as they truly are, in accordance with their authentic identity, and not the false one we give them, or they give themselves, when we know God and are in the closest relationship with him. Indeed, we come to know the true identity of ourselves and of others in an increasing manner the closer we grow to God, the more we are transformed by the divine energies, and the greater our experience and maturity in this union with God.

When we spend all of our time asking the questions – what am I? We cannot find the answer to the question – who am I? It is impossible for us to truly know what we are for, until we know who we are. When we begin by asking – what am I? we de-humanise ourselves and de-identify ourselves. We are never a WHAT in relation to God, who created us. We are always a WHO, and each of us is a unique creation, a unique and non-transferable WHO. No one can replace us, and we cannot be defined in a category, as if we were just another thing.

Our identity in relationship with God is found in the truth that we are each of us made in the image and likeness of God.…

God created man in his own image. In God’s image he created him; male and female he created them.

There will be a need to return to this passage, when we consider the ideas of heterosexuality, homosexuality and transgenderism. But for now, this passage has meaning in relation to our identity, our true personhood. We are created in the image of God. It is our God-like-ness which defines and describes who we are. We are made by God to be like him in our human existence and experience. To be reflections of the life of God in the world, as we participate and share in the divine life which he gives to those who seek unity with him. This God-like-ness reveals to us our value. It is not found in what we do. It is not found in the provisional categories which we use to define ourselves. But it is found in God himself and so our unique value is eternal and immeasurable. When we say – I am this or that – we do not describe ourselves in any meaningful way at all. If we wish to discover who we truly are, as the basis for healing our fragmented and confused state, then we must turn inwards and towards God, in prayer and with a commitment to union with God above all else. This is not to act as if a little prayer and a little religious behaviour will restore us to peace. But if we are serious about discovering who we are then we must encounter the one who made us and find in a relationship with him the identity we seek.

Our healing begins when turn to God in our pain and confusion, and ask that in revealing himself to us, in a close and transforming union, by the Holy Spirit dwelling within us, we might also discover who we are. The beginning of this journey does not remove all doubt and confusion. It does not immediately make clear to us what we should do about thoughts and acts and feelings. But it teaches us that we are not defined and comprehended by our thoughts, deeds and feelings.

We begin the journey of discovering God and our true selves from the place where we find ourselves. It does not matter what thoughts we have, however confusing. It does not matter what acts we engage in, however disturbing. Nor does it matter what feelings we have, however insistent. All that matters is that we determine to set out on the journey towards God and our authentic identity, whatever the cost and however much effort is required.